Penguins are flightless birds that have adapted to live in aquatic environments, primarily in the Southern Hemisphere. They have undergone a number of adaptations throughout their evolutionary history that have allowed them to thrive in these challenging environments.

The earliest known penguin fossils date back to the Paleocene epoch, around 60 million years ago. These early penguins were much smaller than modern penguins, with some species standing only about 16 inches (40 cm) tall. They had long beaks and slender bodies, and were likely better adapted for swimming and diving than for walking on land. The tallest discovered genus of a penguin is the Petradyptes, that lived during the late Oligocene to early Miocene epochs, approximately 27-19 million years ago. The name “Petradyptes” means “rock diver,” as it is believed that these penguins dove from rocky cliffs into the ocean to catch fish.

Petradyptes stood at around 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall, making it one of the largest penguins ever discovered. Its wings were modified into flippers, which it used to swim and dive in the ocean in search of prey. Petradyptes had a long, pointed beak and sharp teeth, which it likely used to catch fish and other prey.

Fossils of Petradyptes have been found in New Zealand, where they likely evolved and lived in the temperate and subtropical waters around the country. The extinction of Petradyptes is believed to have been caused by a combination of factors, including changes in ocean currents and sea temperatures, as well as competition for resources from other marine predators.

Over time, penguins evolved to become larger and more robust, with shorter beaks and flippers that were better suited for diving and swimming. They also developed unique features such as a thick layer of insulating feathers, a streamlined body shape, and a counter-current heat exchange system that helps them regulate their body temperature.

Today, there are 18 species of penguins, which are found primarily in Antarctica and the surrounding Southern Ocean. These species have adapted to a wide range of habitats, from the icy waters of Antarctica to the rocky shores of the Galapagos Islands. However, all penguins share certain key adaptations that have allowed them to thrive in these environments, including a streamlined body shape, flipper-like wings for swimming, and a thick layer of insulating feathers.

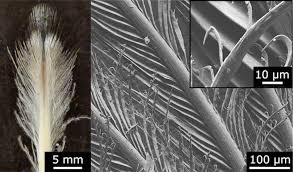

Their feathers are tightly packed and overlapping, which helps to create a smooth, hydrodynamic surface that allows them to move quickly and efficiently through the water. The feathers are also highly waterproof, which helps to keep the penguins dry and warm in the cold ocean.

One of the most distinctive features of penguin feathers is the presence of a special type of feather called a “plumule”. These feathers are small, fluffy feathers that are located near the base of the larger feathers. Plumules are responsible for insulating the penguin’s body and keeping it warm in the frigid water.

Another unique feature of penguin feathers is their ability to shed salt. Penguins live in saltwater environments, and their feathers are exposed to high concentrations of salt. To prevent salt buildup, penguins have a special gland near their tail called the “preen gland” that produces an oily substance. The penguins use their beaks to spread the oil over their feathers, which helps to repel water and prevent salt buildup.

Overall, the feather structure of penguins is highly adapted to their aquatic lifestyle, providing them with warmth, waterproofing, and hydrodynamic efficiency.

Penguins are believed to have been discovered by humans around the 16th century, during the period of European exploration and colonization. The first recorded sighting of penguins was by the explorer Antonio Pigafetta, who accompanied Ferdinand Magellan on his expedition around the world from 1519 to 1522.

Penguins were initially believed to be a type of fish, due to their aquatic lifestyle and their streamlined bodies. However, it was later realized that they were in fact birds that had evolved to live and hunt in the ocean.

As European explorers and whalers ventured further south, they encountered more penguin colonies in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in Antarctica and surrounding islands. The first recorded landing on Antarctica was made by a Russian expedition led by Fabian von Bellingshausen in 1820, and it was during this expedition that the first emperor penguins were observed.

Since then, penguins have become one of the most popular and recognizable animals in the world, and are now a major tourist attraction in many parts of the Southern Hemisphere. They have also been the subject of extensive scientific study, helping us to understand more about their unique adaptations to life in the ocean, their behavior, and their conservation status.

Penguins have a few natural enemies in the wild, including:

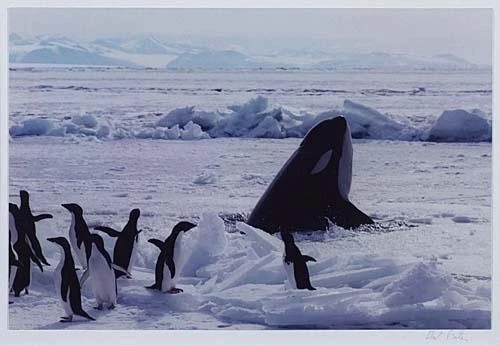

- Leopard seals: These are the primary predators of penguins in Antarctica. They can ambush penguins when they are swimming in the water or basking on the ice.

- Killer whales (orcas): These marine mammals are known to prey on several species of penguins, particularly in the Southern Ocean.

- Skuas: These predatory birds are known to attack penguin chicks and steal eggs.

- Giant petrels: These scavenger birds may attack penguin chicks, injured or sick adults, or steal eggs.

- Humans: Although humans are not natural predators of penguins, they have had a significant impact on penguin populations through activities such as hunting, oil spills, and climate change.

Penguins have a diet that mainly consists of fish, krill, squid, and other small aquatic creatures. The specific types of prey that they eat depend on the species of penguin and their geographical location.

For example, the Adélie penguin primarily feeds on Antarctic krill and small fish, while the Emperor penguin primarily feeds on fish, squid, and krill. The Chinstrap penguin feeds mainly on krill and small fish, while the Galapagos penguin feeds on small fish and crustaceans.

Penguins are excellent swimmers and divers, and they can dive to depths of up to 500 meters (1,640 feet) to catch their prey. They are also opportunistic feeders and will eat whatever is available in their environment. However, their diet is heavily influenced by the availability of prey in their habitat, which can be affected by factors such as climate change and overfishing.